Joana Brígida Capela1, Mariana Reis1, Inês Almeida1, Luísa Gaspar2, Ecaterina Scortenschi2, Marta Soares2, Ana Ramalho2, Vera Santos2, Cláudia Calado2, Maria Alfaro2, João Rosa2.

1Pediatrics Service, Hospital de Faro, Centro Hospitalar Universitário do Algarve, Faro, Portugal,

2Pediatrics and Neonatal Intensive Care Service, Hospital de Faro, Centro Hospitalar Universitário do Algarve, Faro, Portugal.

ADDRESS FOR CORRESPONDENCE

Joana Brígida Capela, Rua Leão Penedo, 8000-386 Faro, Portugal.

Email: jbcapela@chua.min-saude.pt | | Abstract | Introduction: Drowning is the third leading cause of accidental death worldwide, particularly among children. It is a significant public health issue, often occurring in bathing areas with high influx of tourists who are not aware of local risks. Non-fatal drowning incidents can result in permanent neurological damage in children. Our objective was to characterize the pediatric population involved in submersion incidents and hospitalized in a level II hospital, including the short-term hospitalization unit, ward and pediatric intensive care unit. Additionally, we aimed to compare our demographic findings with available data.

Methods: We conducted a seven-year and eight months retrospective study on children admitted to Hospital de Faro, between January 2015 and August 2022.

Results: Our findings indicated a higher incidence of submersion accidents in the early years of life and among males. Most accidents occurred in swimming pools during the summer. Nearly half of the victims were foreigners and the primary cause of submersion was inadequate supervision. The most severe cases involved longer submersion times, a higher occurrence of cardio-respiratory arrest, more complications and extended hospital stays. Among these cases, two children experienced hypoxic-ischemic injury and one resulted in death.

Conclusion: Our data aligns with existing information from Portugal and other European countries. It is crucial to implement preventive campaigns, ensure proper supervision and enforce strict government policies. In bathing areas with tourists presence, preventive measures should be tailored accordingly. Prompt rescue of victims and the initiation of basic life support are vital in positively influencing the prognosis. | | | | Keywords | pediatrics, submersion, cardiac arrest, prevention

Abbreviations

ALS - advanced life support

BLS - basic life support

CPA - cardiopulmonary arrest

CT CE - cranioencephalic computed tomography

GCS - Glasgow Coma Scale

PICU - pediatric intensive care unit

SpO2 - oxygen saturation

STIU - short-term hospitalization unit

WHO - World Health Organization | | | | Introduction | Drownings rank as the third leading cause of accidental death worldwide1, accounting for 7% of all causes of death, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). They are also the second leading cause of unnatural and preventable death in childhood.2,3 The WHO estimates that approximately 236,000 people die each year from drowning, highlighting a public health issue that is often underestimated and undervalued by governments, politicians and the scientific community. Disadvantaged countries, particularly those with limited economic resources, account for around 90% of these cases, predominantly occurring in bodies of water such as seas, lakes and wells. In Europe, the International Live Saving Federation – Europe (ILS – Europe) reports a high prevalence of drowning-related mortality, with approximately 23,000 deaths per year. Moreover, this figure as shown an increasing trend, reaching up to 25% in some European countries.

In Portugal, drownings stand as the second leading cause of accidental death among children and teenagers, representing 16.9% of all drowning cases. Swimming pools are the primary location of such incidents, accounting for 32.5% of occurrences. These statistics align with those observed in other developed countries.4,5 Over the past two decades, there has been a significant and consistent decline in the number of drowning deaths among children and young individuals, dropping from an average of 28 per year to 14, particularly since 2016.5 Similarly, the number of hospitalizations has also decreased from an average of 49 per year to 11.5. However, it is worth noting that in 2020, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of drowning-related child deaths was exceptionally high, with 14 fatalities compared to the previous three-year average of 7.3.5 According to the Association for the Promotion of Child Safety (APSI) in Portugal, the highest number of drowning deaths occurs in the 15-19 age group, while the highest number of hospitalizations is seen in children aged 0-4. Furthermore, 60.5% of accidents occur among male children and 34.2% occur in the 0-4 age group.5 July is the month with the highest incidence of drowning cases, accounting for 24.6% of occurences.5

The issue of drowning extends beyond fatal cases, as non-fatal drownings can result in permanent neurological damage for surviving children.5 Since 2003, APSI has been conducting analysis and studies on drowning incidents involving children and young people, aiming to comprehend the magnitude of the problem in Portugal and guide national-level water safety interventions. These studies have provided insight into the Portuguese context, identifying various risk factors associated with drowning in children and young individuals.5 APSI organizes an annual water safety campaign called “Death by drowning is quick and silent”. Given that no single prevention strategy is sufficient to mitigate drowning risks and their consequences, the implementation of multiple and complementary strategies is necessary. These include adapting the physical environment to align with the characteristics and behaviors of children and adolescents, ensuring active and continuous supervision, implementing appropriate intervention protocols in case of drowning and promoting water-related skills.5 An integrated approach involving measures at different stages (before, during and after accidents) is crucial to significantly contribute to the reduction of drowning-related mortality and morbidity.5,6

According to WHO, the main risk factors for drowning in children are age (1-4 years old), being male, having easy access to water and lack of supervision. Failure to supervise is identified as the leading cause of childhood submersion.3 Additional risk factors include low socioeconomic status, belonging to ethnic minorities, low education levels, living in rural areas, consuming alcohol or drugs near water, having epilepsy or other neurological diseases, suffering from heart disease (such as cardiomyopathies and channelopathies), or being a tourist unaware of local water risks.3

In a retrospective study conducted be Liliane et al. in 2020, certain parameters were found to be correlated with brain performance and long-term neurological prognosis in cases of submersion. These parameters include submersion time, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), temperature, blood pH, high glucose levels and lactate levels. They serve as indirect indicators of the extent of hypoxic-ischemic injury and should be determined, especially in severe cases, to guide medical decision-making.2

Given the significance of this public health issue, our objective was to characterize the pediatric population involved in submersion accidents, hospitalized in the short-term hospitalization unit (STIU), ward and pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) of a level II hospital in Faro, Algarve, Portugal. Additionally, we aimed to compare the demographic findings with existing data from Portugal. The geographical area covered by the hospital holds great importance in the study of submersion accidents, as it encompasses a large bathing area with multiple beaches and pools. Moreover, it experiences a high influx of both national and international tourists, particularly during the summer holidays. | | | | Methods & Materials | We conducted a retrospective study on children and adolescents admitted to the STIU, ward and PICU, of a level II hospital in Faro, Portugal, from January 2015 to August 2022. Data were obtained by reviewing notes using the SClinico® program. The selected cases were divided into two groups upon hospital admission (groups A and B), based on whether they were admitted to the PICU or the STIU and ward, respectively. The following parameters were analyzed:

- Gender, age and residential area

- Relevant personal background

- Month with the highest incidence of cases, location of the incident and presence of a lifeguard

- Main cause of submersion, duration of submersion and state of consciousness upon removal from the water

- Occurrence of cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA) or respiratory arrest and performance of basic life support (BLS) or advanced life support (ALS) maneuvers

- Clinical presentation at hospital admission, including GCS score, respiratory distress, oxygen saturation (SpO2), temperature and capillary blood glucose level

- Analytical changes upon admission, such as pH, lactate and sodium levels

- Radiological findings, including chest X-ray and cranioencephalic computed tomography (CT CE)

- Established treatments, such as intubation, vasopressor support and administration of antibiotics

- Average length of hospitalization, complications during hospitalization and number of deaths

The statistical analysis of the data was performed using Microsoft® Excel 2019 version.

Table 1. Comparison of data obtained between patients admitted to the PICU, STIU and ward.

| |

A Group |

B Group |

| Admissions |

20.6% (N=6) |

79.3% (N=23) |

| GCS =8 |

83.3% (N=5) |

0 |

| Temperature <35ºC |

50% (N=3) |

0 |

| Hyperglycemia (capillary blood glucose >200mg/dL) |

50% (N=3) |

8% (N=2) |

| Respiratory distress |

100% (N=6) |

26% (N=6) |

| Invasive ventilation |

83% (N=5) |

0 |

| Aminergic support |

66.7% (N=4) |

0 |

Acidosis (pH level <7.35)

Carbon dioxide retention

Bicarbonate reduction |

83% (N=5)

50% (N=3)

66.7% (N=4) |

56.5% (N=13)

17.4% (N=4)

30.4% (N=7) |

| Increased lactate level (>1.6 mmol/L) |

66.7% (N=4) |

43.4% (N=10) |

Hyponatremia (<136 mmol/L)

Hypernatremia (>144 mmol/L) |

50% (N=3)

16.7% (N=1) |

35% (N=8)

9% (N=2) |

| Findings on chest X-ray (hypotransparency, infiltrate) |

100% (N=6) |

78.3% (N=18) |

| Performed CT-CE Hypoxic-ischemic lesions |

50% (N=3)

66.7% (N=2) |

17.4% (N=4)

0 |

| Complications |

66.7% (N=4) |

26% (N=6) |

| Deaths |

17% (N=1) |

0 |

| Antibiotic treatment |

66.7% (N=4) |

60.8% (N=14) |

| Average length of stay (days) |

5.5 |

1 |

* A Group – patients admitted to the PICU

# B Group – patients admitted to the STIU and Ward

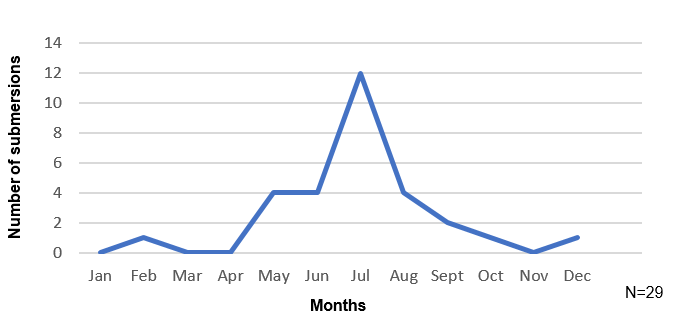

| | | | Results and Discussion | Twenty-nine children were included in the study. The most affected age group was between 1-4 years, with a peak incidence at 1 and 3 years. The mean age was 4.8 years, with a maximum age of 17, a minimum of 1 year and a median of 3 years. The majority of the victims were male children (62%, N=18) and were previously healthy. 16.7% (N=5) had neurological or developmental problems, including epilepsy, autism spectrum disorder, hyperactivity and attention deficit disorder, while none had known heart diseases. Among the children admitted to the PICU, only one child had autism spectrum disorder and another child had an unknown background history. The peak incidence occurred in July during the summer (Figure 1). The majority of the children were Portuguese (52%, N=15), but a significant percentage were foreigners (48%, N=14). Of the foreign children, 50% (N=7) were from the United Kingdom, 21.4% (N=3) were from Ireland, 14.3% (N=2) were from the Netherlands, 7.1% (N=1) were from Belgium and 7.1% (N=1) were from Germany. 50% (N=3) of children admitted to the PICU were foreigners. Over the past eight years, there were peaks of incidence in 2015 and 2019 (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Number of submersions by month. This figure represents the variation in the number of submersions during the year. The peak of incidence was in the summer, in July.

Figure 2. Number of submersions by year. This figure represents the variation in the number of submersions during the last eight years. The peak of incidence was in 2015 and 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic. Then, with the lockdown the numbers fell, but started to increase in 2020.

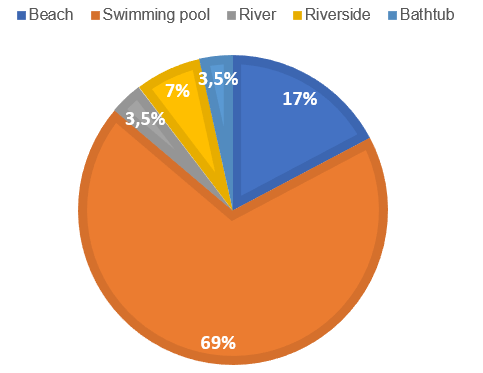

The majority of submersions occurred in swimming pools (69%, N=20), followed by the beach (17%, N=5) (Fig. 3). The presence of a lifeguard at the location was unknown in 50% of the cases and only in 12% was a lifeguard present. The main cause of submersion was lack of supervision (86%, N=25). In one case, the cause was unknown, in two cases it was due to seizures and in one case, it was due to a lack of swimming ability.

Figure 3. Percentage of submersions by local of accident. This figure represents the most common places of submersions. Most of them occurred in swimming pools (69%; N=20), especially in private places; then the most frequent site was the beach (17%; N=5), followed by riverside (N=2), river (N=1) and bathtub (N=1).

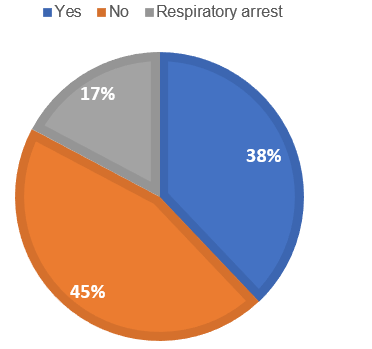

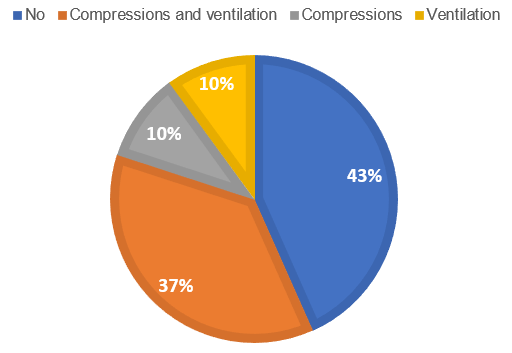

The average submersion time was 2.1 minutes, with 38% (N=11) of cases having unknown durations. In children admitted to the PICU, the submersion time was longer (>4 minutes) or unknown. 72% (N=21) of children were pulled out of the water with impaired consciousness. 38% (N=11) of the children experienced CPA at the scene, while 17% (N=5) experienced only respiratory arrest (Figure 4). Among the children admitted to the PICU, 83.3% (N=5) had experienced on-site CPA. 35% (N=10) of the children received BLS with compressions and ventilations, while 10% (N=3) received either compressions or ventilations alone (Figure 5). 33.3% (N=2) of the children with CPA received ALS on-site by the medical emergency team and were subsequently admitted to the PICU.

Figure 4. Percentage of cases who suffered CPA. 38% (N=11) of the children suffered on-site CPA in the accident local; 17% (N=5) suffered only respiratory arrest.

Figure 5. Percentage of cases who needed BLS. 37% (N=10) of the children received BLS (compressions and ventilations) by local people, family or lifeguard; 10% (N=3) received only compressions or only ventilations. By analyses of figures 4 and 5, we can conclude that 1% of the children who went on CPA only received compressions or ventilation. 2% of the children without CPA went on BLS.

Of the cases, 20.6% (N=6) were admitted to the PICU, 3.4% (N=1) to the ward and 75.9% (N=22) to the STIU. Table 1 represents the data obtained and a comparison between patients admitted to the PICU, STIU and ward.

In the PICU, five of the children were intubated, with two being intubated at the incident site and three at the hospital. The mean duration of intubation was 3.4 days. The complications observed in the patients of the PICU group during hospitalization included hypokalemia, hypertension/hypotension, convulsions, fever, allergic reaction to antibiotics and thrombophlebitis. In the STIU and ward, 91.3% (N=21) had a GCS between 15-13 and 8.7% (N=2) had a GCS between 12-9. Among the children in the STIU and ward, 26% (N=6) received supplemental oxygen therapy. The complications observed in this group included fever and hypokalemia.

None of the Portuguese children or adolescents experienced neurological or other sequelae. However, it was not possible to determine the clinical progression of the foreign children due to the difficulty in establishing contact via telephone or email with their families.

The results in this study are consistent with the literature, namely the higher incidence in the first four years of life, in the male gender, swimming pools as the most frequent waterplace and the lack of supervision as the main motif. Also according to the literature, summer was the most prevalent time of the year and in our review July was the predominant month. Despite the number of submersions, only one death occurred in a teenage boy with 17 years old, corroborating that fortunately most cases have a favorable outcome. The most severe occurred with longer or unknown submersion duration, CPA and the need for BLS, need for endotracheal intubation and admission to the PICU. These patients also had lower GCS and temperature, more frequent hyperglycemia and acidosis, higher lactate levels and there were two cases with hypoxic-ischemic injury. In groups A and B, more than a half of the patients were started on antibiotic treatment, despite the recommendations against its use, likely due to abnormal chest X-ray findings.

The Algarve is a beach holiday destination. Many children have had limited contact with swimming pools and water sea in their home countries and lack the sense of danger around water. This could explain why almost half of our admissions occurred in foreigners, in addition to the families being in a relaxed attitude because they are on vacation.

Our results were consistent with the national data in showing a higher number of cases in 2020, comparing to the average for the last years, although with no increase in the number of deaths. This time period corresponds to the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown and could probably be explained by a higher exposure to private swimming pools and less to public swimming pools with lifeguard surveillance. We could not find an explanation to the peak of cases observed in 2019.

As for the limitations of our study, we acknowledge the small sample size and the lack of information regarding the clinical progression of foreign children, who accounted half of the hospital admissions. | | | | Conclusion | Proper supervision of children is crucial for preventing submersion accidents, along with community strategies. Timely rescue, initiation of BLS and appropriate therapeutic measures are necessary to prevent secondary injuries. It was noted that only 12% of the cases had a lifeguard present, possibly due to many accidents occurring in swimming pools within private condominiums, hotels, or private residences. To address this, preventive measures can be implemented, such as barriers to restrict access to water5, appropriate buoyancy aids for children (e.g., armbands, life vests)5, swimming lessons and water safety education in school curricula3,5, teaching safety measures around water5, training residents and tourists in self-rescue techniques3,5, providing BLS sources for parents and the general population2,4,5, developing a national water safety strategy with awareness campaigns7, ensuring proper supervision of children with epilepsy in water3, enacting legislation for swimming pool safety5 and establishing a National Water Safety Plan in accordance with WHO’s guidelines.

The awareness campaigns conducted in recent years have contributed to a significant reduction in submersion incidents in Portugal, emphasizing the need for such campaigns to be prioritized as part of government health policies. The legislation should be revised to incorporate more stringent policy rules for both private and public bathing areas. | | | | Compliance with Ethical Standards | | Funding None | | | | Conflict of Interest None | | |

- Bierens, J. et al. Resuscitation and emergency care in drowning: A scoping review. Resuscitation 162, 205-217 (2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raess, L., Darms, A. & Meyer-Heim, A. Drowning in children: Retrospective analysis of incident characteristics, predicting parameters, and long-term outcome. Children 7, 1-11 (2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PMC free article]

- Evans, J., Javaid, A. A., Scarrott, E., Bamber, A. R. & Morgan, J. Fifteen-minute consultation: Drowning in children. Arch. Dis. Child. Educ. Pract. Ed. 106, 88-93 (2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhalaf, H. et al. The epidemiology of drowning among Saudi children: Results from a large trauma center. Ann. Saudi Med. 41, 157-164 (2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PMC free article]

- APSI. Afogamentos de Crianças e Jovens em Portugal - Relatório 2002-2021 - Evolução, medidas e recomendações. 1-21 (2022).

- Alhamdani, M. & Kelly, C. Kohler's disease presenting as acute foot injury. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 35, 1787.e5-1787.e6 (2017). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loux, T. et al. Factors associated with pediatric drowning admissions and outcomes at a trauma center, 2010-2017. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 39, 86-91 (2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7199/ped.oncall.2024.34

|

| Cite this article as: | | Capela J B, Reis M, Almeida I, Gaspar L, Scortenschi E, Soares M, Ramalho A, Santos V, Calado C, Alfaro M, Rosa J. Analysis of submersion accidents at a level II hospital and literature review. Pediatr Oncall J. 2024;21: 93-97. doi: 10.7199/ped.oncall.2024.34 |

|