Amit Agrawal1, Lekha Pandit2, Satish Bhandary3, Vittal Nayak4, Tony P Mathew5.

1Department of Neurosurgery, KS Hegde Medical Academy, Mangalore,

2Department of Neurology, KS Hegde Medical Academy, Mangalore,

3Department of ENT, KS Hegde Medical Academy, Mangalore,

4Department of Ophthalmology, K.S. Hegde Medical Academy, Mangalore,

5Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, A B Shetty Memorial Institute of Dental Sciences, Mangalore, Mangalore.

ADDRESS FOR CORRESPONDENCE

Dr Amit Agrawal, Associate Professor, Department of Neurosurgery, K S Hegde Medical Academy, Deralakatte, Mangalore-575018.

Email: dramit_in@yahoo.com | | Abstract | | Subdural empyema is a life-threatening complication of paranasal sinusitis, otitis media, or mastoiditis. It is a collection of purulent material between the dura mater and the arachnoid mater. The classic clinical syndrome is characterized by acute febrile illness that is punctuated by rapid, progressive neurologic deterioration and, if left untreated it will eventually lead to coma with fatal outcome. High-resolution, contrast-enhanced CT scanning has revolutionized the diagnosis of subdural empyema. Surgical evacuation of subdural empyema and aggressive management with antibiotics for a period of 3-6 weeks with close monitoring of clinical status will reduce the mortality and results in good outcome. We report a case and review the relevant literature. | | | | Keywords | | Intradural complications, subdural empyema, chronic sinusitis | | | | Introduction | | Subdural empyema is a life-threatening complication of paranasal sinusitis, otitis media, or mastoiditis. It is a collection of purulent material between the dura mater and the arachnoid mater. In the pre-antibiotic era, the mortality rate approached 100%; this still may be the case in developing countries. However in the developed world, the mortality rate has improved tremendously and it is about 6-35% (1, 2, 3). Rapid recognition, surgical evacuation of subdural empyema and aggressive management with antibiotics for a period of 3-6 weeks with close monitoring of clinical status will reduce the mortality and gives the patient a good chance of recovery with little or no neurological deficit (4). | | | | Case Report | A 14 years old child presented with progressive headache, high-grade fever, left periorbital swelling and foul smelling nasal discharge for five days duration. He was in altered sensorium and had multiple episodes of generalized tonic-clonic seizures without gaining consciousness since morning. He underwent nasal surgery one week back at a peripheral hospital for deviated nasal septum and he was apparently alright for two days. At the time of admission in ICU, he was febrile (103ºF), Pulse rate 110/min, BP 170/90 mm Hg and respiratory rate was 32/min. Chest examination revealed bilateral coarse crepitations. Other systemic examination was unremarkable. Neurologically, he was in altered sensorium. His Glasgow Coma Scale was E1V1M3 and pupils were bilateral 4 mm sluggishly reacting to light. He had neck stiffness and Kerning's sign was positive. He was moving all four limbs. He was having continuous right focal motor seizures involving face and upper limb. Local examination revealed extensive left periorbital edema with redness and raised local temperature. There was no conjunctival congestion or purulent discharge. He was also having purulent nasal discharge that was sent for culture and sensitivity. Immediate endotracheal intubation was performed and child was put on mechanical ventilation. Seizures were controlled with midazolam infusion and loading dose of phenytoin. Plain CT scan that was done two days prior to admission to our hospital at referring peripheral hospital showed opacification of paranasal sinuses including frontal sinus and left orbital hyperdensity pushing the eyeball anteriorly and thin subdural collection on left fronto-temporal region and anterior frontal convexity with no mass effect or midline shift. In view of clinical status and imaging findings, a diagnosis of meningitis was made and left fronto-temporal subdural empyema was suspected. Anti-meningitic doses of broad-spectrum antibiotics were started according to weight of the child (Inj. ceftriaxone, Inj. amikacin and Inj. metronidazole). He was continued on anti-convulsants and anti-edema measures. Over a period of two days he recovered in sensorium; was opening eyes spontaneously and obeying commands but fever was persisting. Over next two days he successfully weaned off from ventilator. After extubation he had motor aphasia. In view of persisting fever, headache and aphasia a repeat contrast CT scan was performed and it showed extensive subdural empyema extending over left fronto-temporo-parietal region, anterior inter-hemispheric fissure and left sub-frontal region (Figure 1). Although paranasal sinuses were relatively clear, both frontal sinuses still showed opacification. He underwent large left fronto-temporal-parietal craniotomy and evacuation of thick non-foul smelling pus and thorough irrigation with saline. Empyema was multi-loculated and brain was highly congested and edematous. It was covered with thick pus flakes. Dura was closed with pericranial graft. Gradually left orbital swelling became localized and reduced in size. It was drained at most fluctuant point and thick pus was drained and sent for analysis. Following evacuation of empyema, his fever and headache subsided and aphasia recovered over a period of two weeks. There was no recurrence of seizures. Cultures from all sources including blood culture were sterile. He was continued on injectable antibiotics for six weeks except metronidazole, which was stopped after ten days. Follow up CT scan after successful completion of antibiotics showed resolution of subdural empyema and clearance of paranasal sinuses except minimal enhancement persisting in inter-hemispheric fissure. Now the child has joined the school after recovery.

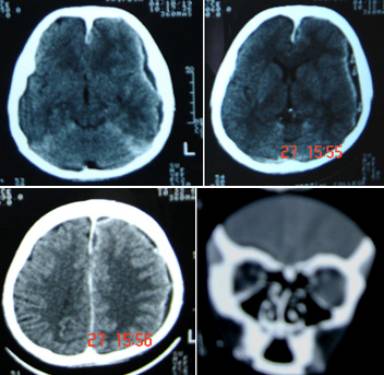

Figure 1: Contrast CT scan axial cuts and coronal reconstruction showing extensive subdural collection extending over left fronto-temporo-parietal region, anterior inter-hemispheric fissure and left sub-frontal region periphery is enhancing with contrast.

| | | | Discussion | | Subdural empyema is a life-threatening complication and accounts for 15-22% of focal intracranial infections (5). It could be as a complication of otitis media (1,6), mastoiditis (7), septicemia, cranial trauma or surgery, recent sinus surgery 3, by spread or extension from an intracerebral abscess, by hematogenous spread from pulmonary sources or from septic thrombosis of cranial veins (8,9,10,11). The classic clinical syndrome is an acute febrile illness that is punctuated by rapid, progressive neurologic deterioration. Clinical features include fever, altered mental status, focal neurologic findings, headache, meningismus, intracranial hypertension and seizures (2,12). Headache, initially focal, is a prominent early symptom in as many as 90 percent of patients. Later, the headache becomes diffuse. If the patient is untreated symptoms will progress over days to include drowsiness, increasing stupor and eventually coma. Seizures, either focal or generalized, have been reported in as many as 50 percent of patients. Examination often reveals a temperature greater than 38ºC (100.5ºF). Aphasia may occur when the dominant hemisphere is involved as in the present case that recovered with aggressive treatment. Meningismus is present in 80 to 90 percent of patients. Occasionally, palsies of the third and sixth cranial nerves occur. In addition, more than 85 percent of patients have contralateral motor deficits. This child did not have focal motor deficits. Pus culture from nasal discharge and subdural collection did not grow any organism. Common causative organisms in subdural empyema are anaerobes, aerobic streptococci, staphylococci, Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae and other gram-negative bacilli, however culture may be sterile if the patient is on antibiotics (13). As in the present case plain CT scan was not enough to show the subdural pus collection as the lesion was very ill defined and vague. High-resolution, contrast-enhanced CT scanning is the standard technique for diagnosis of subdural empyema. On the CT scan, the empyema is manifested by a hypodense area over the hemisphere or along the falx as the margins and extent are better delineated with the infusion of contrast material (Figure 1). CT scan will also delineate any cerebral involvement. Cranial bone involvement can also be seen with CT scan. CT scan is the modality of choice if the patient is comatose or critically ill and MRI is not possible or is contraindicated (14,15). However it may occasionally yield equivocal or normal but in most cases it facilitates the diagnosis and accurately pinpoints the location of the infection. Contrast enhancement may persist even after 3-6 months after successful completion of treatment. In spite of poor prognostic factors ie coma at the time of presentation and sterile cultures (16,17) surgical evacuation of subdural empyema in this child with large craniotomy and aggressive management with antibiotics for a period of 3-6 weeks with close monitoring of clinical status helped him recover completely (4,18). This case emphasizes that early diagnosis and aggressive treatment measures will reduce the mortality in subdural empyema and with excellent outcome. | | | | Compliance with Ethical Standards | | Funding None | | | | Conflict of Interest None | | |

- Nathoo N, Nadvi SS, van Dellen JR, Gouws E. Intracranial Subdural empyemas in the era of computed tomography: A review of 699 cases. Neurosurgery 1999;44:529-36. [CrossRef]

- Hlavin ML, Kaminski HJ, Fenstermaker RA, White RJ. Intracranial suppuration: A modern decade of post-operative subdural empyema and epidural abscess. Neurosurgery 1994;34:974-81. [CrossRef]

- Dill SR, Cobbs CG, McDonald CK. Subdural empyema: analysis of 32 cases and review. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 20: 372-386. [CrossRef]

- Fenerman T, Wachym PA, Grade GF, Dobrow T. Craniotomy improves outcomes in subdural empyema. Surg Neurol 1989;32:105-10. [CrossRef]

- Gormley WB, del Busto R, Saravolatz LD, Rosenblum ML. Cranial and intracranial bacterial infections: In Youmans JR editor, Neurological surgery, 4th Ed, Philadelphia, WB Saunders Co 1996;5:3191-220.

- Green Lee JE. Subdural empyema: Current treatment options in Neurology 2003;5:13-22. [CrossRef]

- Pathak A, Sharma BS, Mathuriya SN, Khosla VK, Khandelwal N, Kak VK. Controversies in the management of subdural empyema: A study of 41 cases with review of literature. Acta Neurochirur (Wien) 1990;102:25-32. [CrossRef]

- Parker GS, Tami TA, Wilson JF, Fetter TW: Intracranial complications of sinusitis. South Med J, 1989; 82(5): 563-9. [CrossRef]

- Gower DJ, Mc Guirt WF, Kelly DLJr: Intracranial complications of ear disease in a pediatric population with special emphasis on subdural effusion and empyema. South Med J, 1985; 784): 429-34.

- Hodges J, Anslow P, Gillett G. Subdural empyema-continuing diagnostic problems in the CT scan era. Q J Med 1986;228:38-93.

- Krauss WE, McCormick PC. Infections of the dural spaces. Neurosurg Clin N Am 1992;3:421-33. [CrossRef]

- R. Skelton, W. Maixner, D. Issacs, Sinusitis-induced subdural empyema, Arch. Dis. Child 67 (1992) 1478-1480. [CrossRef] [PMC free article]

- de Louvis J, Gortvai P, Hurley R. Bacteriology of abscesses of the central nervous system: a multicentre prospective study. Br Med J 1977;2:981-4. [CrossRef]

- Taha ZM, Bashier El FM. Subdural Empyema, diagnostic difficulties and surgical treatment controversy. Pan Arab J Neurosurg 2002;6:21-32.

- Moseley IF, Kendall BE. Radiology of intracranial empyemas with special reference to computed tomography. Neuroradiology 1984;26:333-45. [CrossRef]

- Mauser HW, von Houwelingen HC, Tulleken CA. Factors affecting outcome in subdural empyemas. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 1987;50:1136-41. [CrossRef]

- Renauddin JW. Cranial Epidural and sub dural Empyema. In: Wilkins RW and Rengachary SS editors. 2nd Ed, NewYork, McGraw Hill, 3rd vol, p. 3313-5.

- Bok APL, Peter JC. Subdural empyema: burr holes or craniotomy- J Neurosurg 1993;78:574-8. [CrossRef]

|

| Cite this article as: | | Agrawal A, Pandit L, Bhandary S, Nayak V, Mathew T P. EXTENSIVE SUBDURAL EMPYEMA, PARANASAL SINUSITIS AND ORBITAL CELLULITIS COMPLICATING NASAL SEPTUM SURGERY IN A CHILD. Pediatr Oncall J. 2005;2. |

|